Cross-Examination

Background

CROSS-EXAMINATION RESOURCES RELATED CONCEPTS LEGAL TRAINING RESOURCE CENTER |

Cross-examination is an opportunity for the defense attorney to question the prosecution's witnesses during a trial. Cross-examination is an effective way for the defense to present evidence by using government witnesses. On cross, the attorney should be asking questions that develop the defense's theory of the case theory of the case. Cross may be the defense's only opportunity to present important facts, inferences and impressions.

Direct examination and cross-examination have very different purposes and techniques. Direct examination is the opportunity for the witness to tell their story. The attorney should simply be helping the witness to tell the story by asking the witness open-ended questions.

Cross-examination, in contrast, is a targeted attack on the prosecutor's theory of the case. The focus should be on the attorney, leading the witness to answer the questions to support the defense's theory. During cross-examination the defense attorney seeks to persuade the jury that the witness' testimony is:

- inconsistent with other testimony or evidence

- biased against the defendant

- the result of a witness' personal motive

- demonstrates that the witness (if a co-defendant) had the opportunity to commit the crime

- illustrates the witness'lack of knowledge of the facts and the evidence, or

- shows the witness' inability to see, hear, perceive, and observe important parts of the incident

Regardless of whether the criminal defender is preparing for direct or cross, he should prep the case by answering the following questions:

- What is the overall theory?

- How does this witness fit into that theory?

- Where does this witness' story fit in presenting the theory? Does this witness establish the theory or simply provide support?

- How will the witness's testimony help you to develop your client's story? To counter the prosecutor's story?

- What evidence do you need to introduce or rely on during direct examination? During cross-examination?

- What evidence will the prosecutor rely on during direct examination? During cross-examination? What questions can you ask or what evidence can you use to counter the prosecutor's evidence?

The Right to Cross-Examination

The right to cross-examination is typically found in a country's constitution or evidence code. Generally, the right guarantees an opportunity to ask questions of government witnesses at trial. It may also preclude the introduction of written statements by the prosecution, if the defense did not cross-examine the witness at the time of the statement.

Examples:

United States - In the United States the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that "in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right...to be confronted with the witnesses against him."

China - In China, CPL Articles 47 and 156 give criminal defenders the right to conduct direct and cross-examination of witnesses in criminal cases. CPL Articles 156, 157 and 160 give criminal defense attorneys the right to use evidence to impeach the prosecution's witnesses.

India - In India, Section 138 of the Indian Evidence Act provides the criminally accused the right to confront witnesses.

Justice Antonin Scalia of the United States Supreme Court has called cross-examination the crucible in which the reliability of evidence is tested . Because cross-examination is the only method by which the defendant may directly challenge the veracity of a government witnesses testimony, it is one of the most fundamental and important rights of the accused.

Scope of Cross-Examination

Generally, a defense attorney may ask questions which are relevant to facts and/or biases that relate directly to the testimony of a particular witness. In some jurisdictions cross-examination may be limited to the scope of the prosecution's direct examination.

The collateral facts rule permits the government to object when a defense attorney is cross-examining or impeaching a witness on issues that are collateral or irrelevant to the question of law or fact being argued. For example, if a witness is testifying as an eyewitness to a crime, the fact that they have not paid their taxes in the last few years would be irrelevant to the case. If a defense attorney attempted to discuss the issue on cross in an attempt to discredit the witness, a judge would likely rule that a witness' taxes are irrelevant to the veracity of his eyewitness testimony.

Elements of a Successful Cross-Examination

Cross-examinations are not supposed to be cross. Your job as the attorney is to persuade the fact finder that a particular aspect of the witness' testimony is wrong. Being rude or too adversarial is not the best way to persuade. Only become aggressive when necessary, for instance, if the witness' is non-responsive or has a clear motive. Remember you should constantly be thinking about the best way to persuade the fact finder to believe your theory of the case.

Every question should fulfill a substantive, technical or emotional role:

Substantive: question resulting in testimony or facts related specifically to the crime charged

Technical: questions must be technically legal under the jurisdiction's rules of evidence; question should be phrased carefully to elicit the desired response

Emotional: questions should always have an emotional impact on the fact finder; the emotional impact may stem from the substantive nature of the question or how the question was presented by the attorney

Remember to be aware of your demeanor and the atmosphere in the courtroom. Presenting a calm, assured presence is often more effective in persuasion than verbose theatricality, but measure the fact finders individually and determine which style works best.

Cross-Examination and the Theory of the Case

What is the theory of the case? Here is how three public defenders have defined theory of the case:

"That combination of facts and law which in a common sense and emotional way leads the judge to conclude a fellow citizen is wrongfully accused" - Tony Natale, Federal Defender

"The central theory that organizes all facts, reasons, arguments and furnishes the basic position from which one determines every action in the trial" - Mario Conte

"A paragraph of one to three sentences which summarizes the facts, emotions and legal basis for the citizen accused's acquittal or conviction on lesser charge while telling the defenses story of innocence or reduced culpability" - Vince Aprile

Cross-examination should be client-centered and driven by the law and the facts. The strategy for cross-examination must fit within the larger strategy developed for the case. Thus, the goals of cross-examination are often to emphasize facts that support your theory and deemphasize or diminish facts that do not. A theory of the case is a common-sense articulation of the law and the facts that favors your client.

Closed-Ended Questions

The goal of cross-examination is to target the prosecutor's case and to advance the defendant's theory of the case without giving the witness the opportunity to explain away their answers. You want the witness to simply affirm or deny the question you are asking. Criminal defense attorneys should NEVER ask who, what, where, when, why, how, describe, and explain during cross-examination. These are words requiring explanation that you do not want to elicit during cross-examination.

Closed-ended questions are designed to force the witness to answer yes or no. A cross-examination should consist SOLELY of closed-ended questions, unless the attorney is absolutely sure of the witness' answer to an open-ended question.

A closed-ended question is rally more of a statement, simply requiring the witness to confirm or deny.

Following are some examples:

- The bar was crowded on the night of the fight?

- Who threw the first punch - the victim or the defendant?

- And, you were still there when the fight ended?

If a witness prevaricates or does not answer the question, you should ask a follow-up question to confirm. If it is an important point, you want to make sure the fact finder is hearing the answer, not the explanation. But be careful, repeating the question over and over is not effective; it is the fact finder's responsibility to draw their own conclusion about why the witness is not answering.

Pitfalls of Cross-Examination

Using compound or long questions can be confusing to both the witness and the jury. Short questions will focus the attention of the witness on one fact at a time. Do not simply repeat the direct testimony of the witness. This only reinforces the prosecution's case. Do not start a question with "why", "tell me", "so" or "oh yeah."

Do not repeat good questions that receive good answers. Defense attorneys will often want to do this to emphasize a surprising answer that is beneficial to their case. However, repeating the question only gives the witness an opportunity to change or explain their answer.

As a general rule, a defense attorney should never ask a question when he or she doesn't already know the answer. However, under certain circumstances, a defense attorney may ask a closed-ended question, even if he does not know the answer. Such questions are sometimes called "No Lose Questions" because the answer will not break the case. For example, when cross-examining a police officer about the report he made at the scene, you might ask, "You wanted to get the most accurate information possible?"

Structuring/ Formatting a Cross-Examination

Transitioning from one topic to another is particularly difficult on cross, because the defense is helping the witness to tell a story. One way to change the topic, it to use a transition or headline statement. Although these are not questions, transition statements are generally permissible because they notify the witness and the fact finder that the subject has shifted.

For instance during cross, the defense attorney might say, "Now I'd like to talk about the night of October 2, 2009" or "Let's talk about the lighting conditions at the market on the evening of July 29, 2009."

There are many ways of structuring a cross-examination that has multiple parts. The defense attorney should always keep in mind that the fact finder is most likely to remember the first and the last facts established on cross. Therefore, the defense attorney should develop a strategy that emphasizes strong points at the beginning and end. Following is a sample outline for a multi-part cross-examination:

- Introduction / set up /transition

- 1st Subject

- Transition

- 2nd Subject

- Transition

- 3rd Subject

- Transition

- Closing Subject

"Looping" is a method of sequencing questions to highlight certain facts. A defense attorney "loops" questions when he uses the answer to the prior question to begin another question. Looping has three stages:

- Establish a fact.

- Use fact to ask second question (emphasizing the fact).

- Continue to build in a continuous loop.

One method of structuring cross examination is the Chapter Method. The Chapter Method organizes cross examination into a cluster of favorable points (called chapters) that ultimately help you tell the judge or jury your side of the story.

To follow this method:

First, define your purpose of cross examination for the witness. Is it to expose bias or motive? To bring out inconsistencies of facts? Or to simply show that the witness cannot be believed? Your purpose may be different for each witness. It should be determined based upon all of the facts and the purpose should coincide with your theory of the case.

Second, once you determine the primary goal of your cross examination of a specific witness, decide what points you would like to make. The points will help you reach your primary goal. Each point will become a chapter and will deserve at least one page. A point may be the existence of a fact, the introduction of a new fact, or the weakening of an existing fact.

Third, place the point that you wish to make on the top of the page. Each point will be the title of each chapter. For example, if you want to show a witness could not have seen the suspect very well because it was dark outside, write on the top of the page, "Witness Couldn't See Suspect Because Dark Outside."

Forth, draft a number of cross examination questions in a logical progression that lead up to, and give context to, the ultimate point you want to make. Begin with general questions and move to specific questions. Use simple, one fact per sentence, leading questions. For Example,

- The robbery occurred at 10pm at night?

- At 10pm at night, it is dark outside?

- You were outside when the robbery occurred?

- When the robbery occurred, you were outside standing in the dark?

Fifth, and finally, be sure to include a form of reference to your points and cross examination questions. The reference may be used in the event that the witness tries to disagree with you. The reference can be a small notation or shorthand pointing to the specific resource that you obtained the information from: police report, witness interview, photo, etc...

The goal in cross examination should not be to have the witness recite the facts in a chronological order. This simply mimics the prosecution and solidifies their side of the story. That is why the chapter method is so effective. It helps the judge or jury focus on your specific points that illustrate your theory of the case.

At the end of your cross examination you should achieve your primary goal through your chapters and the specific points you made. These chapters and their points can then be used in closing arguments to remind the judge or jury of what the evidence is and how it is consistent with your theory of the case.

Witness Control

Being in control of the questioning is extremely important. As the attorney you want to be assertive, but not aggressive. However, if a witness is adversarial and non-responsive, maintaining control is crucial. Phrase questions as narrowly as possible and try not to give them any wiggle room. However, you should try not to become visibly flustered by the witness. While it is important to repeat questions that are not being answered, your tone should remain even, unless the witness is hostile. Very rarely should you ever allow exasperation or impatience to color your tone; you run the risk of seeming like a bully to an innocent witness, instead of damaging the witness' credibility as you intended. Be very careful when acting aggressively.

Watch out for these type of responses:

- Quibbling over facts

- Rambling speeches

- Answering different questions.

In addition, the defense attorney may impeach the witness by confronting them with a prior written or oral statement if it contradicts their current testimony.

The more a witness resists giving straight answers, the more he or she will damage their credibility in front of the judge or jury. However, explaining an answer is not the same as resisting; make sure to look for the difference.

Preparing for Cross-Examination

Cross-examination is a real, live event. Therefore, your ability to anticipate, plan, prepare, and practice in advance is crucial to a persuasive presentation. A good trial attorney prepares extensively for cross-examination in advance. By the trial, you should know the government's basic theory and have a sense of what a witness or co-defendant is going to say. Generally, there should not be any surprises about the witness' story. The witness should have given a statement to the police or the prosecutor. As the defense attorney, you should go through the statement and identify what points are helpful or harmful to the client.

For instance, a co-defendant story may contradict other evidence in the prosecutor's case or the co-defendant testimony may identify his own involvement, but not the client's. In these circumstances, the co-defendant may actually be helpful at trial. On the other hand, the co-defendant may have a motive to shift blame onto your client. Or the co-defendant's statement may be the product of coercion or abuse by the police.

Regardless, a good defense attorney thoroughly investigates all pre-trial statements. If the witness deviates from the script of his prior statement, the defense attorney will have ample grounds to argue that he is inconsistent or unreliable.

Consider these questions when preparing for cross-examination:

- What are the facts beyond dispute?

- What is the context for the facts beyond dispute?

- Is the fact important to the judge?

- Is the fact necessary to your theory of the case?

- Which witness are able to corroborate or deny these facts?

- What is believable?

- What is expected?

A successful cross-examination requires preparation by the attorney both prior to and during trial. You should try to interview all witnesses as soon as possible after the crime. Beware of interviewing the victim or any party represented by a lawyer. Certain jurisdiction do not permit formal depositions of victims or witnesses before trial. However, if you are able to obtain a deposition, it may prove useful at trial. Depositions can be presented as direct evidence if the witness in unavailable. Or depositions can be used to impeach a witness.

Now that the evidence has been gathered, the criminal defense attorney should determine whether potential witnesses help or hurt the defendant's case.

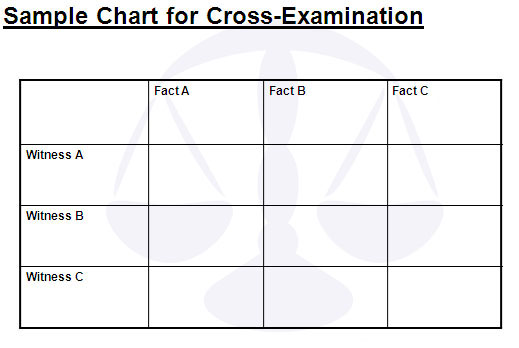

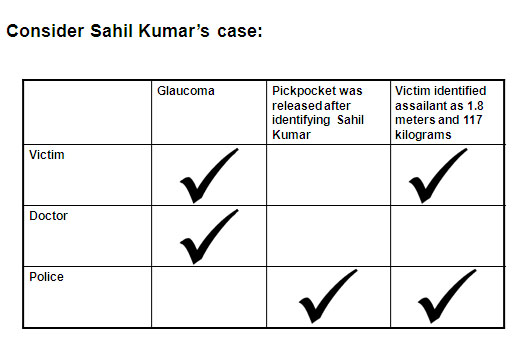

Following is a sample grid to prepare for cross-examination:

Although significant preparation can be done before the trial itself, the prosecutor's opening statement will also provide valuable information. While listening to the prosecutor's opening statements:

- Do not take notes of facts you agree with -- you are just wasting time.

- Take note of the theme

- Note facts that are new or unknown to you

- Note facts that differ from your own

- Note facts that you doubt can be proven

- Note facts that are overstated

- Take note of the specific words that are uttered -- for later use in your cross.

Impeachment

Impeachment is an allegation, supported by proof, that a witness who has been examined is unworthy of credit. Impeachment may be indirect, as through a second witness or presentation of other physical evidence. Or impeachment may be direct, which is typical in cross-examinations or even direct examination (if permissible.) Cross-Examination is one of the primary places that a defense attorney can impeach a witness. Generally, a defense attorney may impeach prosecution witnesses subject to limitations in the evidence code. Under certain circumstances, an attorney may even impeach their own witnesses.

When preparing for a case, imagine how any one of these areas might impact the witness's credibility:

Bias, interest, motive, prejudice, corruption, plea deal, etc.

The most common method of impeaching the credibility of a witness is bias, particularly when a witness has a personal relationship with the victim. Similarly, a witness who has been given a special deal by the prosecution has a strong incentive to lie.

Prior convictions and bad acts

The admissibility of prior convictions and bad acts varies from country to country. However, a defense attorney should always keep these in mind. In the United States the rules regarding the admissibility of prior convictions as impeachment evidence is complex. However, as a general rule convictions that substantiate or undermine the honesty of a witness are the most powerful. Prior bad acts are also helpful on cross, if admissible.

In the United States, prior bad acts are not admissible to substantiate a subsequent claim of the same bad act. Thus, evidence of prior burglaries cannot be used to prove a defendant is guilty of burglary. However, prior bad acts may be admissible in the United States for other, so-called "non propensity" reasons: motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, plan knowledge, identity or absence of mistake. The rules of evidence surrounding prior bad acts will vary greatly from jurisdiction and the defense attorney should study these carefully.

Prior dishonest conduct

Prior dishonest conduct, like prior convictions for tax evasion or perjury, may be admissible for credibility purposes.

Specific contradictions / reality

A witness's statement may assert a fact that is contradicted by reality. For instance, a witness may claim it was raining when in fact it was sunny.

Capacity to perceive, recollect and communicate

A powerful method of impeachment during cross-examination is to attack a witness' ability to perceive, recollect, and communicate. For instance, in a case of eyewitness misidentification, the defense attorney may attack a witness' vision by showing the witness was not wearing her glasses at the time of the incident.

Prior inconsistent statements

A defense attorney can also impeach a witness through prior inconsistent statements during cross-examination. This type of impeachment simultaneously undermines the witness's credibility and establishes a question of fact for the jury. There are at least two ways of looking at prior inconsistent statements. In some cases, the lawyer will want to argue that the first statement is the most accurate of the two. In other cases, the lawyer may argue that the second statement is more reliable. In some cases, the lawyer may simply want to show that the witness is totally unreliable.

Following is a three-step guide to impeachment through inconsistent statements when the goal is to bolster the credibility of the witness's first statement:

- Step 1: Commit the witness to the statement by asking leading questions.

- Step 2: Commit the witness to the circumstances surrounding the statement that increases the chance that the statement was accurate.

- Step 3: Confront the witness with the contradiction.

Refreshing Recollection

By the time a case goes to trial, several months may have passed since the alleged incident. Therefore, it is common for witnesses to not remember certain facts. Sometimes, a witness may have provided testimony to police officers or investigators early in a case. In some jurisdictions the court may permit the defense attorney to "refresh" the recollection of the witness by providing them with a copy of their own statements. If refreshing recollection is permissible in your jurisdiction, you should be familiar with the steps necessary to establish foundation for the procedure in court.

Browne v. Dunne: Limits on Impeachment

In some jurisdictions the special rule of Browne v. Dunne may apply. The Dunne rule is: a cross examiner cannot rely on evidence that is contradictory to the testimony of the witness without giving the witness an opportunity to justify the contradiction. If this rule applies, the criminal defense attorney must ask the witness to explain the contradiction.

Cross-Examination Hypothetical

CASE FILE: Sahil Kumar was shocked when police came to his home and arrested him for robbery. He was taken to the police station, where a 76-year-old man identified him as having stolen his wallet at the Chawri market that morning. Kumar admitted he was at the market that morning, but insists he is innocent. He has visible bruises on his face, and claims the police forced him to confess to the crime by torturing him for two days, before producing him in front of the magistrate. As a result of your investigation you have identified four potential witnesses who may appear at trial: a pickpocket who identified Sahil Kumar as the thief, the victim, the victim's doctor, and the police officer who arrested Kumar.

Your investigator has discovered the following important facts:

- The pickpocket was arrested on the same morning as your client and was subsequently released from custody after he identified Sahil Kumar as the thief,

- After the incident the victim told the police that the thief was 1.8 meters tall and weighed 118 kilograms.

- The victim has glaucoma, a degenerative eye condition, which was first diagnosed by his doctor in 2002.

- Your client is actually 1.7 meters tall and weighs only 80 kilograms.

Sample Cross-Examination of Victim

Q: I'd like to talk about your vision. You were diagnosed with glaucoma in 2002?

A: Yes.

Q: The doctor said you've lost most of your peripheral vision?

A: Yes.

Q: That means you can't see as well as you used to?

A: No.

Headline Statement: Now I want to talk about what happened after you were robbed at the market.

Q: Did you call the police?

A: Yes.

Q: The police came?

A: Yes.

Q: And then they took you back to the police station?

A: Yes.

Q: They brought the defendant to you in the station?

A: Yes.

Q: And then the police asked you if this man robbed you at the market?

A: Yes.

Q: And you said that he did?

A: Yes.

Transition + Q: I'd like to go back to the market for a second. When the police arrived, did they interviewed you there?

A: Yes.

Q: And at that point you had just been robbed an hour before?

A: Yes.

Q: So your memory was fresh?

A: Well ...

Q: Fresher than it is now?

A: I suppose so.

Q: You gave a description of the thief to the police?

A: Yes.

Q: And you wanted the description to be as complete as possible, so the police would have the best chance of catching the thief?

A: Yes.

Q: And you told them the thief was 1.8 meters tall?

A: Yes.

Q: And you also told them that the thief was at least 127 kilograms?

A: Yes

Q: Thank You.

See Trial, Direct Examination, Opening Statements, Closing Statements and Theory of the Case

| |

English • français |

|---|