Confessions

Background

Despite increased evidence that confessions may be unreliable, they remain the gold standard of evidence for police investigations. Confessions are sometimes called the "Queen of Evidence".

Many countries have complex rules for the admissibility of confessions. These rules serve several functions. First, they serve to guarantee that wrongful conviction does not occur. Second, they act as a deterrent to abusive interrogation by the police.

Confessions may be obtained by interrogation techniques that violate the defendant's free will or procedural rights. A defense attorney should be prepared to argue that these confessions are inadmissible as evidence against their client.

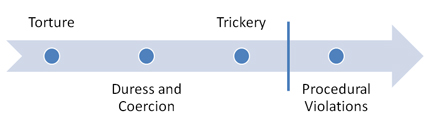

Confessions may be inadmissible for a variety of reasons but generally these can be classified into two categories. The first category of reasons asks the factfinder to determine whether the confession was voluntary in nature. If it is voluntary, then it may be admissible. If it was involuntary, then it should be inadmissible because it is inherently unreliable.

Defense counsel may argue that a confession is involuntary if it is the product of torture, coercion, duress or even police trickery. Each interrogation must be examined on its own facts. The most obvious case to argue for the inadmissibility of evidence is when a confession is the direct result of torture or other inhuman and degrading treatment. Cases of coercion or duress fall in the middle category where international jurisdictions differ as to what level of coercion or duress is necessary to trigger inadmissibility of a confession. Finally, in some jurisdictions police deception or trickery, even if not coercive, may lead the confession to be inadmissible.

In common law/adversarial criminal justice systems the defense attorney should argue that the confession should be exclusion. In a civil law / inquisitorial system the defense attorney should argue that the confession should be nullified.

In either case, failure to get a confession excluded from consideration at trial does not prevent the defense attorney from arguing that the confession is inherently unreliable and that the factfinder should consider the circumstances surrounding the interrogation when deliberating at the conclusion of the trial.

The second category of reasons asks the fact finder to examine the procedural aspects of the interrogation to determine if police followed procedures that are required under the law. Under this test, the confession may be inadmissible even if it was given voluntarily.

Three Factors in False Confessions

The famous Goldberg Commission Report identified three factors that would increase the likelihood of a false confession.[1] The first factor examined the defendant's personality. Defendants are more likely to confess when they have difficulty differentiating reality from fiction, they are self-destructive or desire to confess out of overwhelming guilt for past behaviors. The second cluster of factors are the conditions of confinement and methods of interrogation that bear on the defendant prior to the confession. The final factors are external forces that put may put pressure on defendants to make false confessions.

The Corroboration Requirement

Because of the risk of false confession, it is often the case that the trial court will require some additional corroborating evidence before an individual may be convicted on a confession alone. Sometimes called the Corpus Delecti ("The Body of the Crime"), the standard of proof required for corroboration varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. The demand for corroboration decreases the risk of false confessions and requires police to conduct investigations beyond simple interrogation.

One study determined that false confessions may occur without any coercive police practices. For this reason, some academics have concluded that all confessions should be accompanied stronger corroborative evidence.[2] Finally, some practitioners have concluded that only video-taped or audio-recorded confessions should be admissible.

International Sources

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

Article 14, Section 3 -

- In any criminal trial, a defendant is entitled to the following rights:

- (a) To be properly informed of the charges against him, in a language that he understands;

- (b) To have enough time to properly prepare his defense and communicate with a lawyer whom he chooses;

- (c) To have a prompt trial after arrest;

- (d) To be present at the trial and to have a defense either as a defender for himself or have a lawyer defend him; to be informed of his right to have a lawyer; and to have a lawyer assigned to him if the defendant's financial situation does not allow him to afford a lawyer;

- (e) To question witnesses of the opposing parties and to place his own witnesses on the trial stand under the same circumstances as that of the opposing parties' witnesses;

- (f) To have an interpreter assist the defendant if he cannot speak the court's language;

- (g) To have his privilege against self-incrimination and right against forced confessions upheld.[3]

Examples of standards for the admissibility of confessions

India

No confession made to a police officer is valid as evidence at a trial. All confessions must be made to a Magistrate not below the rank of Judicial Magistrate. The Magistrate taking the confessions must give the accused due time out of the custody of the police, and make an effort to ensure that the accused was not coerced or intimidated in anyway, before receiving the confession. At the bottom of the confession the Magistrate must write out that he has informed the accused that this confession may be used against him and he is not obligated in any way to incriminate himself.[4]

United States

Voluntariness Test - In the United States, a confession is admissible if a judge deems it to have been made voluntarily. In Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U.S. 278 (1936), the U.S. Supreme Court first excluded confessions procured and introduced in a state criminal case concluding that admission of the confessions would violate due process. The rule is grounded in three principals. First, exclusion of involuntary confessions tends to deter police misconduct. Second, a confession should be freely made by a rational person. Finally, confessions obtained with duress are inherently unreliable.

The admissibility of incriminating statements made at the time a defendant had his "rational intellect" and/or "free will" compromised by mental disease or incapacity is to be governed by state rules of evidence and not by the Supreme Court's decisions regarding coerced confessions and Miranda waivers. Also, coercive police activity is a necessary predicate to the finding that a confession is not "voluntary" within the meaning of the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment. [5]

When determining whether a confession was voluntary, the court should look at the "totality of the circumstances". [6] In certain circumstances, police misconduct may be so egregious that the confession evidence should be excluded without regard for how that conduct the defendant. However, when conduct is less egregious, a court should consider if the conduct actually induced an involuntary confession.

McNabb-Mallory Rule - A second line of cases in the U.S. Federal Courts holds that a confession obtained during Federal custody is inadmissible if the defendant is not promptly produced in court after arrest.[7] If argued under this line of cases, it is unnecessary to prove that the confession was, in fact, involuntary. It is enough to show that the police or prosecution unlawfully detained the suspect for a prolonged period, extracted a confession, and then attempted to use the confession against the defendant in court. See Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 5(a):

Rule 5. Initial Appearance

(a) In General. (1) Appearance Upon an Arrest. (A) A person making an arrest within the United States must take the defendant without unnecessary delay before a magistrate judge, or before a state or local judicial officer as Rule 5(c) provides, unless a statute provides otherwise. (B) A person making an arrest outside the United States must take the defendant without unnecessary delay before a magistrate judge, unless a statute provides otherwise.

State Rules

Kenya

In Kenya, if a confession is voluntarily made, it may be admitted into evidence. Section 25 of the Evidence Act defines a confession as ‘words or conduct, or a combination of words and conduct, from which, whether taken alone or in conjunction with other facts proved, an inference may reasonably be drawn that the person making it has committed an offense." To protect the accused against any adverse outcome due to forced confessions, the law provides safeguards to ensure that confessions are made willfully and with full knowledge that the exercise of the right to remain silent does not amount to an admission of guilt.

Germany

In Germany, there is no general mandatory exclusionary rule. The German Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP) instead allows for courts to operate on a discretionary basis for exclusions. Courts are willing to exclude confessions obtained in violation of a provision of the CCP, reasoning that violations of the CCP may discredit the reliability of the evidence obtained.[8] Furthermore, in 1992, a German Federal Court of Appeals held that confessions obtained by police without issuing required warnings cannot be used as evidence.[9] However, the Court stated that if it could be shown that the suspect knew of his/her rights, the lack of warnings did not necessarily lead to exclusion.[10]

The exception to German rule of no mandatory exclusions is section 136a of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP). This section excludes any confessions obtained by ill-treatment, induced fatigue, physical interference, administration of drugs, torment, deception or hypnosis.[11] The police are prohibited from using such methods and the court will exclude any confession made in an interrogation that uses such techniques, even if the confession itself was voluntary.

United Kingdom

English law, like American law, requires a finding of voluntariness before admission of a confession.[12] The prosecution has the burden of proof to show that the confession was voluntarily made. The judge must decide on the issue at the voir dire hearing, which is outside of the presence of the jury. Confessions are governed by section 76(2) of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) of 1984. Section 76(2) reads:

"If, in any proceedings where the prosecution proposes to give in evidence a confession made by an accused, it is represented to the court that the confession was or may have been obtained

(a) by oppression of the person who made it; or

(b) in consequences of anything said or done which was likely, in the circumstances existing at the time, to render unreliable any confession which might be made by him in consequences thereof,

The court shall not allow the confession to be given in evidence against him except in so far as the prosecution proves to the court beyond reasonable doubt that the confession (notwithstanding that it may be true) was not obtained as aforesaid."[13]

Section 82(1) of PACE defines "confession" as "any statement wholly or partly adverse to the person who made it, whether made to a person in authority or not and whether made in words or otherwise." [14]

There are two main rationales to exclude confessions: oppressive police methods and reliability. If the judge admits the confession, defense counsel still has the right to argue oppression or unreliable evidence at trial. It will then be up to the jury to decide the weight that should be given to the confession. In making such a decision, the jury must act compatibly with the right to a fair trial and the right against self-incrimination.[15]

Canada

Traditionally, under Canadian common law, the exclusionary rule for confession admissibility has three components:

1) There must be fear of prejudice or hope of advantage;

2) The fear of prejudice or hope of advantage must have been held out by a person in authority; and

3) The statement must be a result of inducement.[16]

Like in the UK, the prosecution held the burden of proof in establishing voluntariness of a confession and the decision of voluntariness is decided outside of the presence of the jurors by a judge at voir dire.[17] Under Canadian case law, a statement is not considered voluntary if it is not the product of an "operating mind."[18] The phrase "operating mind" is meant to protect against statements that are unreliable due to a lack of rationality. A statement is also not considered voluntary when the accused is unaware of the consequences of making such a confession (i.e. intoxication or mental disorder)- this standard focuses more on the mental ability of the accused, rather than the conduct of the police.[19] Canadian courts have also held that statements made under oppression are involuntary and thus inadmissible.

Under modern Canadian law, the common law rule of confessions works in conjunction with the rules under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[20] The Charter relates to confessions in its privilege against self-incrimination and its right to silence. The burden of proof is different under the Charter: the accused must prove that there has been an infringement of his/her Charter rights and then must demonstrate that the confession was obtained in a manner that violated those rights.[21]

Australia

The common law rule stipulates that only voluntary confessions can be admitted to the court. This principle is reinforced in the Evidence Act of 1995, section 84, which reads that a confession is not admissible unless the court is satisfied that the confession was not influenced by violent, oppressive, inhumane or degrading conduct or a threat of any kind.[22]. In following the common law principle, the cases used several different rationales to justify such exclusions (i.e. right to silence, reliability, etc.). The standard became clearer with the cases of R. v. Swaffield and Pavic v. R.; in those cases, the Australian High Court outlined the following confessions test:

1) Was it voluntary? If so,

2) If is reliable? If so,

3) Should be it be excluded in the exercise of discretion?[23]

This confessions standard emphasizes reliability more than previous tests. The court also includes examination of public policy issues, in addition to issues revolving around trial fairness and unduly prejudicial evidence.[24]

Cambodia

Under the UNTAC Criminal Law and Procedure Code of 1992, article 24(3) addresses confessions. It reads that "[c]onfessions by accused persons are never grounds for conviction unless corroborated by other evidence. A confession obtained under duress, of whatever form, shall be considered null and void. Nullification of a confession must be requested from the judge by counsel for the accused prior to the sentencing hearing."[25] Furthermore, under the 2007 Cambodian Code of Criminal Procedure, article 321 states that declarations given under physical or mental duress have no evidentiary value.[26] Both of these sections reflect the principle in article 38 of the Cambodian Constitution, which proclaims that confessions obtained through physical or mental force shall not be admitted as evidence.[27].

See Right to Silence, Rights of the Accused

Notes

- ↑ Report of the Commission for Convictions Based Solely on Confessions and For Issues Regarding the Grounds for Retrial (1994)

- ↑ Dr. Boaz Sangero, Miranda is Not Enough: A new Justification for Demanding "Strong Corroboration to a Confession", Cardozo Law Review, Vol. 28 No. 6 (May 2007).

- ↑ http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/ccpr.htm

- ↑ India Criminal Procedure Code Section 51

- ↑ Colorado v. Connelly, 479 U.S. 157 (1987)

- ↑ Haynes v. Washington, 373 U.S. 503 (1963)

- ↑ McNabb v. United States, 318 U.S. 332 (1943), Mallory v. United States, 354 U.S. 449 (1957)

- ↑ Comparative Criminal Procedure: History, Processes and Case Studies, Raneta Lawson Mack, 2008

- ↑ Comparative Criminal Procedure: History, Processes and Case Studies, Raneta Lawson Mack, 2008

- ↑ Comparative Criminal Procedure: History, Processes and Case Studies, Raneta Lawson Mack, 2008

- ↑ http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_stpo/englisch_stpo.html

- ↑ Gordon Van Kessel, The Suspect as a Source of Testimonial Evidence: A Comparison of the English and American Approaches, 38 Hastings L.J. 1 (1986)

- ↑ http://www.statutelaw.gov.uk/content.aspx?LegType=All+Primary&PageNumber=1&NavFrom=2&parentActiveTextDocId=1871659&ActiveTextDocId=1871659&filesize=9089

- ↑ http://www.statutelaw.gov.uk/content.aspx?LegType=All+Legislation&searchEnacted=0&extentMatchOnly=0&confersPower=0&blanketAmendment=0&sortAlpha=0&PageNumber=0&NavFrom=0&parentActiveTextDocId=1871554&ActiveTextDocId=1871668&filesize=13420

- ↑ http://www.icclr.law.ubc.ca/Publications/Reports/ES%20PAPER%20CONFESSIONS%20REVISED.pdf

- ↑ http://www.icclr.law.ubc.ca/Publications/Reports/ES%20PAPER%20CONFESSIONS%20REVISED.pdf

- ↑ http://www.icclr.law.ubc.ca/Publications/Reports/ES%20PAPER%20CONFESSIONS%20REVISED.pdf

- ↑ Queen v. Spencer, https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/14233/index.do

- ↑ http://www.icclr.law.ubc.ca/Publications/Reports/ES%20PAPER%20CONFESSIONS%20REVISED.pdf

- ↑ http://www.icclr.law.ubc.ca/Publications/Reports/ES%20PAPER%20CONFESSIONS%20REVISED.pdf

- ↑ http://www.icclr.law.ubc.ca/Publications/Reports/ES%20PAPER%20CONFESSIONS%20REVISED.pdf

- ↑ http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nsw/consol_act/ea199580/s84.html

- ↑ http://www.icclr.law.ubc.ca/Publications/Reports/ES%20PAPER%20CONFESSIONS%20REVISED.pdf. See also R. v. Swaffield, http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/cth/HCA/1998/1.html?query=title(R%20%20and%20%20Swaffield)

- ↑ http://www.icclr.law.ubc.ca/Publications/Reports/ES%20PAPER%20CONFESSIONS%20REVISED.pdf

- ↑ http://www.bigpond.com.kh/Council_of_Jurists/Judicial/jud005g.htm

- ↑ David McKeever, Evidence Obtained Through Torture Before the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, 8 J. Int'l Crim. Just. 615 (2010)

- ↑ http://www.khmerrough.com/pdf/CriticalThinking-Eng/Part5-CriticalThinking.pdf

| |

English • español • français |

|---|