Showups, Lineups, and Photo Arrays

Eyewitness identification evidence is extremely persuasive evidence for a criminal prosecution. Eyewitness testimony is powerful because we assume it to be the most reliable. However, studies have shown that eyewitness evidence is often mistaken and that eyewitnesses are prone to suggestive identification procedures. The problem of eyewitness misidentification is often exacerbated by out-of-court identification procedures. Misidentification is often difficult to detect, as eyewitnesses sincerely believe in their own testimony.

Eyewitness procedures should be carefully scrutinized in order to maximize the reliability of identifications, minimize unjust accusations of innocent defendants and establish evidence that is reliable and conforms to established legal procedures.

The United States Constitution's Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination does not extend to identification procedures that include blood [1] or handwriting [2], fingerprints, x-rays, etc. However, if an identification is unusually invasive it may be inadmissible for other reasons. For instance, in Winston v. Lee, the U.S. Supreme Court held that forcing a defendant to undergo surgery which requires general anesthetic in order to obtain evidence violates the Fourth Amendment prohibition against unreasonable search and seizure when the evidence is not absolutely necessary to convict the defendant.[3]

A factfinder may draw adverse inferences from a defendant's refusal to participate in an identification procedure [4] or a defendants altered appearance after the crime. Courts may use coercive methods such as imprisonment or contempt of court to force participation in identification procedures.

The criminal defense attorney should endeavor, whenever possible, to be physically present during any identification of his or her client. This is the only way to guarantee that the identification is fair and is not coercive. As a practical matter this is not always possible. Presence of a criminal defense attorney at an identification procedure poses certain ethical problems. For instance, if the defense attorney is compelled to become a witness in the trial he may then be forced to withdraw as counsel to the case because of this conflict of interest.

As a general rule identification procedures should not be "unnececessarily suggestive".[5]. In determining what is "fair" or "unfair" in identification procedures (the due process question), the courts consider all the circumstances leading up to the identification. Unfairness will be found only when, in the light of all the circumstances, the identification procedure was so suggestive as to give rise to a real and substantial likelihood of irreparable misidentification. [6]

Contents

Procedures for Challenging Identification Procedures

In order to challenge an identification procedure in a common law system, the lawyer should request a hearing to suppress the identification as unnecessarily suggestive (known as a "Wade Hearing"). A defendant may have to testify at such a hearing to establish the facts surrounding the original identification. In the United States these statements generally cannot be used at the later trial unless the defendant opens the door to inclusion on direct or cross-examination.

Showup

In some cases, usually soon after the alleged commission of a crime, a witness or victim will be presented with one potential defendant. This is known as a showup. Some courts have suppressed identification evidence based on the use of showups due to the inherent suggestiveness of the practice. Showups are the most suggestive of all eyewitness identifications because only one person is shown to the witness. Therefore, the use of showups should be secondary in preference to the use of photo arrays or lineups when possible.

If necessary, a showup should happen as soon as possible after the incident. The more time that elapses between the event and the identification procedure, the more suggestive it will be.

Recommended Police Guidelines for Showups

Following is a series of recommended guidelines for conducting showups as written by the Port Washington Police Department.[7]

- Document the eyewitness's description carefully prior to the showup.

- Whenever practical, transport the eyewitness to the location of the suspect. Showups should not be conducted at law enforcement headquarters or other public safety buildings.

- Specifically instruct eyewitnesses that the real perpetrator may or may not be present.

- Showups should not be conducted with more than one witness present at a time. If identification is conducted separately for more than one witness, witnesses should not be permitted to communicate before or after any procedures regarding the identification of the suspect.

- The same suspect should not be presented to the same witness more than once.

- Showup suspects should not be required to put on clothing worn by the perpetrator. They may be asked to speak words uttered by the perpetrator or to perform other actions of the perpetrator.

- Words or conduct of any type by officers that may suggest to the witness that the individual is or may be the perpetrator should be scrupulously avoided.

- Assess eyewitness confidence immediately following an identification

Lineup

Lineups are less suggestive than showups because more individuals are present in the identification procedure, therefore reducing the suggestive nature of the showup. At least six individuals should be used in a lineup although U.S. courts have upheld lineups using only three individuals. Criminal defense attorneys observing lineup procedures should be careful to note the sex, race, physical features, clothing and age of lineup participants.

Photo Array

One significant difference between a lineup and photo array is that the defendant may not have a right to counsel to be present during the photo array.[8] Photo arrays are also more efficient than lineups in that they permit the police to reuse existing mugshots. It also increases the likelihood that the police station will be able to find a sufficient number of similar individuals for the identification procedure.

Recommended Police Guidelines for Lineup and Photo Arrays

Following is a series of recommended guidelines for conducting lineups and photo arrays as written by the Port Washington, Wisconsin Police Department.[9]

- Choose non-suspect fillers that fit the witness' description and that minimize any suggestiveness that might point toward a suspect;

- Use 'double blind' procedures, in which the administrator is not in a position to unintentionally influence the witness's selection;

- Specifically instruct eyewitnesses that the real perpetrator may or may not be present and that the administrator does not know which person is the suspect;

- Present the suspects and fillers sequentially (one at a time) rather than simultaneously (all at once.) This encourages absolute judgments of each person presented, because eyewitnesses are unable to see the subjects all at once and are unable to know when they have seen the final subject;

- Assess eyewitness confidence immediately following an identification. Carefully document a witness' response before any feedback from law enforcement;

- Avoid multiple identification procedures in which a witness views the same suspect more than once.

Composite Sketch

Inaccurate information from outside an eyewitness' memory can also taint development of a composite. As with photo arrays, live lineups, and showups, composites can be compromised if the witness' description relies on information learned from external sources after the crime or if the person administering the procedure either unintentionally supplies the witness with information or unintentionally incorporates outside knowledge of the case into the production of the composite. For this reason, when a composite is used, double-blind concepts and principles in which both the witness and the person making the composite are unaware of external information about the case may be helpful. It may not be feasible to conduct a completely double-blind procedure for a variety of reasons, in which case witnesses should be told to rely on their independent recollection of the event - not information learned from other sources - and administrators must be mindful of any natural tendency to incorporate prior knowledge into the process.

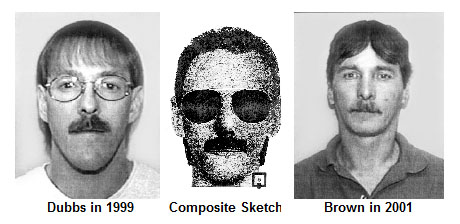

The case of Charles T. Dubbs exemplifies another problem inherent in composite sketches:

Charles T. Dubbs, above left, was convicted of sexually assaulting two women in Dauphin County, PA in 2000 and 2001 based on the above composite sketch, center. Both of the victims identified Dubbs as the assailant. Dubbs spent five years in prison before he was exonerated. [10] Wilber C. Brown, who had admitted to committing the crimes to police, was later convicted.

Sample Jury Instructions

If a criminal defense attorney is representing a client in a jury trial and identification evidence plays a significant role in the case, the defense attorney should try to get a jury instruction on the nature of eyewitness identification. Following is a sample jury instruction used in a U.S. Federal Court:

Identification testimony is an expression of belief or impression by the witness. Its value depends on the opportunity the witness had to observe the offender at the time of the offense and to make a reliable identification later.

In appraising the identification testimony of a witness, you should consider the following:

(1) Are you convinced that the witness had the capacity and an adequate opportunity to observe the offender? Whether the witness had an adequate opportunity to observe the offender at the time of the offense will be affected by such matters as how long or short a time was available, how far or close the witness was, how good were lighting conditions, whether the witness had had occasion to see or know the person in the past...

(2) Are you satisfied that the identification made by the witness subsequent to the offense was the product of his own recollection? You may take into account both the strength of the identification, and the circumstances under which the identification was made.

If the identification by the witness may have been influenced by the circumstances under which the defendant was presented to him for identification, you should scrutinize the identification with great care. You may also consider the length of time that lapsed between the occurrence of the crime and the next opportunity for the witness to see defendant, as a factor bearing on the reliability of the identification....

(3) You may take into account any occasions in which the witness failed to make an identification of defendant, or made an identification that was inconsistent with his identification at trial.

(4) Finally, you must consider the credibility of each identification witness in the same way as any other witness, consider whether he is truthful, and consider whether he had the capacity and opportunity to make a reliable observation on the matter covered on his testimony.

I again emphasize that the burden of proof on the prosecutor extends to every element of the crime charged, and this specifically includes the burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt the identity of the defendant as the perpetrator of the crime with which he stands charged. If after examining the testimony, you have a reasonable dounbt as to the accuracy of the identification, you must find the defendant not guilty. [11]

Expert Testimony

Courts appear to be split as to whether to allow expert testimony on the issue of eyewitness identification, with some courts concluding that this is an issue the jury can understand without the assistance of expert opinion.

See Evidence

Notes

- ↑ Schmerber v. California, 384 U.S. 757 (1966)

- ↑ Gilbert v. California, 388 U.S. 263 (1967)

- ↑ Winston v. Lee, 470 U.S. 753 (1985)

- ↑ South Dakota v. Neville, 459 U.S. 553 (1983)

- ↑ Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293 (1967)

- ↑ Neil v. Biggers, 409 U.S. 188 (1972)

- ↑ Port Washington Police Department, General Order 6.3.4: Eyewitness Identification, May 06, 2009

- ↑ United States v. Ash, 413 U.S. 300 (1973)

- ↑ Port Washington Police Department, General Order 6.3.4: Eyewitness Identification, May 06, 2009

- ↑ Carrie Cassidy, Dubbs Conviction Thrown Out, Patriot-News, Sept 12, 2007.

- ↑ United States v. Telfare, 469 F.2d 552 (D.C. Cir 1972)