Identity Checks

Contents

Background

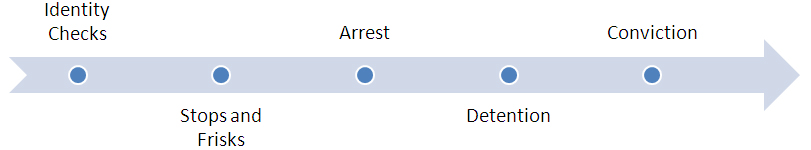

May police officers demand that a citizen produce identification upon demand even if the officer has no cause to believe a crime has been committed or is afoot? In some countries, police have this right. Courts will often state that the invasion of privacy is so small when an officer demands identification that no privacy rights are triggered at all. The law in this area continues to evolve as governments develop extensive identification requirements for their citizens.

While identity checks are legal in many countries, their validity is tainted by the widespread use of racial profiling. Defense Attorneys should be prepared to challenge any identification stop based on race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.[1] The stop may be illegal under domestic or International Law.

County Specific Applications

France

French Criminal Procedure Code, Article 78-2 permits judicial police officers and their agents to ask any person to justify their identity by any means where one or more plausible reasons exist to suspect:

- that the person has committed or attempted to commit an offence;

- or that the person is preparing to commit a crime or a misdemeanor;

- or that the person is able to give information useful for an enquiry into a felony or misdemeanor;

- or the person is the object of inquiries ordered by a judicial authority

Furthermore, under French Criminal Procedure Code, Article 78-3, an individual who refuses to identify themselves may be held by the police until their identity can be ascertained. The detention may not last longer than 4 hours, however, from the time that an identity check was initially made according to Article 78-2. Critics of these provisions allege that identity checks are used by French Police to harass and intimidate minorities.[2].

A study conducted in 2007 and 2008 spent several months observing and counting French officers conducting identity stops at Paris's Gare du Nord and Chatelet-les Halles train stations. Researchers concluded that Arab and Black men had chance of being aribtrarily stopped and asked for their identity card that was 7.8 times higher than that of Whites.[3]

Germany

German Criminal Procedure permits prosecutors and police officials to conduct identity checks on individuals suspected of offenses[4] and permits officers to conduct identity checks on individuals who are not suspected of an offense if necessary to investigate a criminal offense.[5] An individual who refuses to establish his or her identity may be detained no longer than is necessary to establish that identity.[6]

As in many countries, minorities (particularly Muslims) accuse German police of using identity checks to intimidate immigrants. [7].

Spain

In a case involving a police identity check allegedly based on race, the National Court of Spain concluded that the "social contract" requires citizens to disclose their identity to police officers and that the officer is not required to have any quantum of suspicion before he or she can execute the stop. Spain's Constitutional Court ratified the police's action as lawful. The case was later heard by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva, Switzerland.[8] The committee found general identity checks to be legal but concluded that Leecraft's stop had been based on race.

United States

In Hiibel v. Sixth Judicial District Court of Nevada, 542 U.S. 177 (2004), [9] the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that neither the Fourth nor the Fifth amendment prohibited a state from requiring an individual to identify themself by name during stops and frisks. A state's identification requirement must simply be reasonable, meaning that the State's interest must outweigh any intrusion against the individual, to be contstitutional. The case concluded that when an officer has reasonable suspicion to stop an individual, he or she can simultaneously conduct an identity check.[10]. In the Hiibel case the Court did not decide whether an identity check incident to a stop based on less than reasonable suspicion would be constitutionally permissible.

Several states, such as New York, appear to permit identity checks based upon on less than reasonable suspicion. In New York, an officer need only have "articulable reason" for approaching an individual and asking for their identity, [11] although additional rationale may be needed if the officer's tone becomes aggressive.

Notes

- ↑ Article 2, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

- ↑ Ghali Hassan, French Ghettos, Police Violence and Racism, http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid=1214

- ↑ French Racist Discrimination, http://marcovilla.instablogs.com/entry/french-racist-discrimination/

- ↑ German Criminal Procedure Section163b(1)

- ↑ German Criminal Procedure Section163b(2)

- ↑ German Criminal Procedure Code 163c.

- ↑ Jan Yager, German Muslims Call Mosque ID Checks "Humiliating", Global Post, Jan. 11, 2010, http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/germany/100108/islam-terrorism-security-islamophobia.

- ↑ Rosalind Williams Leecraft v. Spain, Communication Submitted for Consideration under the First Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, available at http://www.womenslinkworldwide.org/pdf_programs/prog_ge_acodi_legaldocs_complaint.pdf.

- ↑ Hiibel v. Sixth Judicial District Court of Nevada, 542 U.S. 177 (2004)

- ↑ The court noted that in the ordinary course of an investigation "a police officer is free to ask a person for identification without implicating the Fourth Amendment.Hiibel v. Sixth Judicial District Court of Nevada, 542 U.S. 177 (2004)

- ↑ People v. Debour, 40 N.Y.2d 210 (New York 1976)