Chinese Law Primer

China's criminal justice system consists of public security bureaus, procurates, courts and correctional institutions. At the central level, the Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Justice administer China's police and correctional institutions, respectively. The Supreme People's Court is the highest judicial branch in the country. The Supreme People's Procuratorate is the highest state branch of legal supervision (In China, people's procuratorates are authorized to supervise court trials of criminal cases. Procuratorial supervision over criminal proceedings refers to legal supervision that aims to ensure criminal proceedings conducted by people's courts coincide with procedures prescribed by law and that verdicts and rulings passed by people's courts conform to the relevant legal provisions.) with prosecution as its main function. The respective roles of these branches are as follows:

- the public security branches are responsible for the investigation, detention, and preparatory examination of criminal cases;

- the people's procurates are responsible for approving arrest, conducting procuratorial work (including investigation) and initiating public prosecution;

- the people's courts are responsible for adjudication; and the prison or other facilities are responsible for sentence execution.

Contents

Indigent Criminal Defense System

The legal aid system in China was first established in 1994, aiming to offer free or inexpensive legal services to citizens who have financial difficulties. On December 16, 1996, the National Legal Aid Center of the Ministry of Justice was established to promote the development of legal aid bodies nationwide and to monitor their operations. Since 1996, the National Legal Aid Center has established over 3000 legal aid centers throughout the country. The legal aid centers are responsible for providing legal services in civil, criminal and administrative cases. In criminal proceedings, the accused, if he/ she is a juvenile, deaf mute or is facing the death penalty, shall be entitled to legal aid. In all other cases, the provision of counsel is discretionary.

Function of Legal Aid Centers

There are, in a strict sense, no public defender offices in China. All legal aid centers handle both civil and criminal cases. In turn, the lawyers at these centers are not specialists; they handle any and all types of cases. This structure, or lack thereof, magnifies many of the problems that the system needs to rectify. First, considering the large population of China, the provision of legal aid still lags far behind the demand. Second, the operation and quality of legal aid centers varies greatly from place to place. The reason is that there is no national law to unify and standardize the structure, operating procedures and sources of funding of the legal aid centers. Third, many local governments lack funds to set up legal aid centers. Fourth, the quality of lawyers cannot be ensured. Fifth, there is no mechanism to ensure the independence of legal aid centers.

Stages of the Criminal Process

In China, the criminal process is divided into three distinct stages; the investigation stage, the prosecution examination stage and the trial stage. The demarcation between each of these stages is important as the rights and privileges of both defense counsel and the accused are significantly limited during pre-trial investigation and prosecution examination stages. Though Chinese law does grant lawyers the right to enter criminal proceedings and to meet with their clients during the investigation and prosecution examination stages, their function is significantly curtailed. Moreover, in practice many lawyers are not assigned to the case until a few days before trial leaving the defense lawyer with little time to prepare an adequate defense.

Investigation Stage

In China, as elsewhere, the investigation stage is often the most important part of the criminal process. Most criminal offenses in China are investigated by the Public Security Bureau (police department). Criminal offenses committed by government officials, employees, and agencies, however, are investigated directly by the People's Procuratorate. It is during the investigation stage that investigators (public security officers or procurators) detain and interrogate (often repeatedly) the accused, and otherwise gather evidence and interview witnesses. The investigation stage can last months in China, or even years, during which time the accused is generally held in detention. Though theoretically entitled to bail, few persons are released pending trial. Lawyers, as well as police and prosecution officials often argue that the defense lawyers' function is so curtailed during the investigation stage, that there is no purpose in seeking appointment or being retained until a later stage in the process.

Though defense lawyer's rights are limited by law during the investigation stage, there is nevertheless substantial work that can be done to begin to prepare for the client's defense at trial. According to China's Criminal Procedure Law, the scope of the services that lawyers may offer include providing legal consultation to the client, bringing petitions and complaints on the client's behalf, and applying for bail for the client (see Criminal Procedure Law, art. 96). During this time, lawyers may file petitions or complaints in cases where their client has been tortured or their rights have otherwise been violated. Moreover, though the lawyer will not yet have access to the prosecutor's files, or be able to investigate the facts of the case, he/ she can provide invaluable advice and counsel to his/ her client; obtain all relevant facts and circumstances of the case known to the client; begin to build a relationship with the client which will aid the lawyer's ability to lawfully advocate for the client's rights and interests; and otherwise begin to prepare his/ her defense for trial.

Chinese law does little to define the scope of the permissible content of attorney-client meetings at the investigation stage, stating vaguely that lawyers may "enquire about the case" (see Criminal Procedure Law, art. 96). However, subsequent rules promulgated by the All-China Lawyers Association (China's national bar association) have provided more guidance. Article 28 of the Rules Governing the Handling of Criminal Cases by Lawyers provides that "in interviewing a criminal suspect [during the investigation stage], a lawyer may obtain from the criminal suspect information on relevant circumstances of the case, including":

- The criminal suspect's physical conditions;

- Whether and in what manner the suspect participated in the alleged crime;

- If the suspect admits guilt, a declaration of the facts and circumstances important to determining the level of the crime and sentencing;

- If the suspect does not admit guilt, a declaration of his defense;

- Whether the legal methods of the detention are lawful, and whether the procedure conforms to the law;

- Whether the suspect's personal or procedural rights were violated subsequent to his detention;

- Other information that the lawyer needs to know.

Prosecution Examination Stage

After gathering evidence, the investigators (either the Public Security Bureau or the Procuratorate) submit evidence to the Procuratorate section in charge of approving prosecutions. The standard of review for the Procuratorate is "whether the facts and circumstances of the crime are clear, whether the evidence is reliable and sufficient, and whether the charge and the nature of the crime is correctly determined" (Criminal Procedure Law, art. 137). The prosecutor must also decide whether it is a case in which "criminal responsibility should not be investigated." In making these determinations, the prosecutor must interrogate the suspect and his or her representative, and consult with the victim and his or her representative. If, during this review, the prosecutor discovers that any illegal method was used during investigation, the prosecutor may refer the conduct of the investigator to the appropriate disciplinary authority. If the misconduct rises to the level of a criminal offense, it is referred to the appropriate section of the Procuratorate for investigation (Criminal Procedure Law, art. 76).

Despite the fact that accused persons have the right to counsel at the prosecution examination stage, few lawyers are assigned to represent the indigent accused during this time period. Many legal aid attorneys, following past practice, are reticent to accept cases earlier than the trial stage. Many are concerned that such advocacy would result in more work and greater expense on their part, and little additional benefit would be afforded to the accused (defense attorneys will receive only the charging document and other limited information at the prosecution examination stage. They will not be entitled to more complete discovery until the trial stage)

- Note on Detention v. Arrest - Arrest is a more formal detention procedure in China than in the United States. Though the police in China have enormous discretion to detain a criminal suspect pre-trial, eventually the law requires them to either make a formal arrest, or release the suspect. Moreover, a formal arrest must be approved by the procuratorate. According to Article 60 of the Criminal Procedure Law, to approve a formal arrest, the Procuratorate must find that: 1) "there is evidence to support the facts of a crime;" 2) the "criminal suspect or defendant could be sentenced to a punishment of not less than imprisonment;" and 3) "such measures as allowing him to obtain bail or placing him under residential surveillance would be insufficient to prevent the occurrence of danger to society."

- Pre-trial Attorney/ Client Access - Despite legislation stipulating that lawyers be given pre-trial access to their client, many scholars and practitioners lament that the right of Chinese defense lawyers to meet with their clients in custody has not been successfully implemented in practice. There are many obstacles that prevent adequate implementation of the law. Compounding this issue is the fact that the poor often possess very little practical knowledge about their procedural rights, or about the availability and/or purpose of legal aid. Without such knowledge, they are unlikely to exercise their right to apply for legal aid

Trial Stage

There is no plea bargaining system in China. All cases must go to trial, even when the evidence of guilt is overwhelming and the accused readily confesses to his crime. (Though a simplified trial procedure called summary procedure is available in cases "where the defendants may be lawfully sentenced to fixed-term imprisonment of not more than three years, criminal detention, public surveillance or punished with fines exclusively, where the facts are clear and the evidence is sufficient, and for which the People's Procuratorate suggests or agrees to the application of summary procedure", see Article 174 of the Criminal Procedure Law). It is during the trial stage that lawyers are generally appointed to represent the indigent accused. The law requires courts to assign cases to legal aid providers just ten days before trial (see Article 151 of the Criminal Procedure Law). However, many legal aid lawyers lament that courts often do not abide by this statutory prescribed time period, and in many instances, lawyers are appointed just two or three days before trial. It is important to note that attorneys may request a continuance of trial to subpoena new witnesses, obtain new material evidence, make a new expert evaluation or to do more investigation (see Articles 159, 165 of the Criminal Procedure Law). Few lawyers now utilize these provisions in court. Lawyers should be encouraged to request more time to prepare when legitimate reasons require it, especially in very serious or complicated criminal cases.

Chinese trials are much more streamlined than they are in the United States. Generally, the entire proceeding will not last more than a few hours. Witnesses rarely appear in court. Though theoretically, a court may subpoena witnesses who then shall be questioned and cross-examined by both the prosecution and defense, in practice, the court generally relies solely on the witnesses' written statements (of course, it would be economically and practically unfeasible for witnesses to appear in every case, as all cases must go to trial in China, however, in serious or complicated cases, e.g., defense counsel should be encouraged to routinely make applications to the court to subpoena witnesses, see Article 159 of the Criminal Procedure Law). The prosecution simply reads out the statements, thereby depriving the accused and his lawyer of the opportunity to cross-examine them. Often these statements, themselves are rather limited in detail and content. As China lacks formal rules of evidence, rulings concerning the introduction and evaluation of evidence depend largely on the court.

Standard of Proof

The standard of proof at trial is that "the facts are clear and the evidence is reliable and sufficient." (Article 162 of the Criminal Procedure Law). The defendant may be found innocent outright or by reason of insufficient evidence. It is important to note that from the Chinese perspective, whether or not someone has committed a crime is a matter of ascertainable fact. The court is thus seeking an objective, rather than legal truth - - this affects the courts analysis of evidence, testimony and argument.

Defendant's Obligation to Testify

There is no right to remain silent under Chinese law, either during the pretrial stage (i.e., interrogation) or during trial. At the pre-trial stage, suspects are obligated to answer all relevant questions of the investigator (silence is deemed as stubborn resistance to authorities and compounds the appearance of guilt. In practice, the police employ many techniques to obtain the defendant's "confession"). At trial, many lawyers believe that if the Defendant wishes to be treated leniently, he must admit his actions and express remorse before the court.

Many provisions of Chinese law reward the Defendant's conduct in truthfully confessing one's crime, for example, the provisions of Voluntary Surrender and Meritorious Performance (see Articles 67, 68 of the Criminal Law). Further, lawyers are concerned that if their clients do not confess at trial, they will be treated more harshly by the court, i.e., the defendant should truthfully report their actions or information to the best of their knowledge, so that the facts of the case can be clarified. The police and courts still rely mainly on pretrial confessions and written statements to resolve cases instead of the Western tradition of analyzing forensic evidence and determining guilt through contentious court trials, however, this is changing.

Many Chinese lawyers do not adequately prepare their client to testify to the relevant facts and circumstances of the case, nor do they emphasize the client's ability to reinforce and bolster the defense case. Many times, the defense lawyer will ask their own clients questions that are prosecutorial in nature because they lack an understanding of how to ask purposeful defense minded questions. Lawyers also do little to explain to their clients the procedure of the trial itself. Understandably, this leaves clients anxious and ill prepared; too often this leads to these clients making a bad impression on the court that affects the outcome of the case. Further, defenders are ill trained to deal with situations in which their clients deny all or part of their alleged confessions

Court's Discretion in Determining Judgment

In China, the court is not limited in making its judgment, to the charges in a criminal case. Thus, for example, if the prosecutor charges the defendant with intentional injury because though the victim died the prosecutor does not believe the defendant had the requisite intent to kill the victim - a court may find the defendant guilty of murder if it believes the defendant had the requisite intent to kill

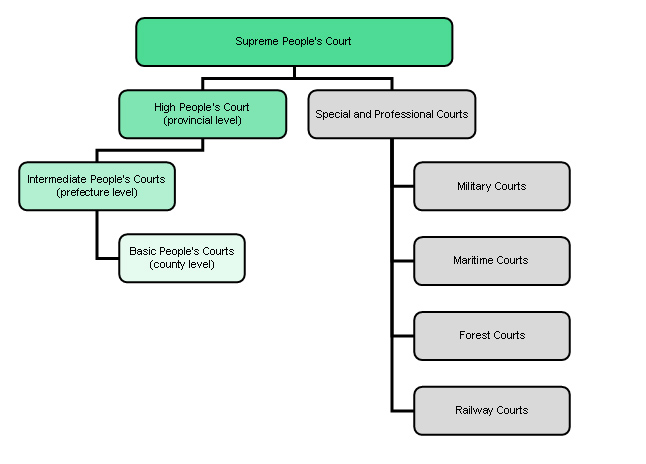

Court Structure and Process

China's court system has four levels. The highest court is the Supreme People's Court which sits in Beijing. At the next level there are the Higher People's Courts which sit in the provinces, autonomous regions and special municipalities (i.e., Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing and Tianjin). Then there are Intermediate People's Courts which sit at the prefecture level (a level of division between the province and county levels - most frequently, these are cities that are given prefecture status and the right to govern surrounding counties) and also in parts of provinces, autonomous regions, and special municipalities. There are also basic People's Courts in counties, towns, and districts. The jurisdiction of each of these courts depends on the nature and complexity of the case.

Appeals

Litigants are generally limited to one appeal, on the theory of finality of judgment by two trials. (There are exceptions to this rule. In some cases there is a third appeal. The litigant can also appeal to the people's procuratorate [prosecutor's office] and the court for reconsideration of the case. Additionally, there are a number of more informal procedures of appeal). In theory, cases on appeal are to be reviewed de novo as to both law and facts. Accordingly, the trial and appeal process are referred to as a trial of first instance (trial) and a trial of second instance (appeal). In practice, however, courts routinely conduct only a paper review of the court file, utilizing the following language in article 187 of the Criminal Procedure Law as justification: "after consulting the case file, interrogating the defendant and heeding the opinions of the other parties, defenders and agents ad litem, [a court] thinks the criminal facts are clear" it is not required to hold a separate hearing in the case.

From a judgment or order of first instance of a local people's court, a party may bring an appeal to the people's court at the next highest level, and the people's procuratorate may protest a court decision to the people's court at the next highest level. (Note: There is no principle of double jeopardy in China. The people's procuratorate can appeal an acquittal). Judgments or orders of first instance of the local people's courts at various levels become legally effective if, within the prescribed period for appeal, no party makes an appeal.

Unlike its American counterpart, China's Supreme People's Court does not actively hear cases. Instead, it functions primarily as an administrative organ, supervising lower courts and issuing opinions on various provisions of law. The Higher People's Court holds preliminary hearings for major civil and criminal cases of a province, an autonomous region or municipality directly under the Central Government. It also conducts retrials or second trials when the people's procuratorate disputes the judgment or the defendant appeals against the verdict or ruling by the Intermediate People's Court at the first trial level. The Intermediate People's Court hears cases of counterrevolutionary crimes and cases involving life imprisonment and the death penalty, as well as actions against foreigners or Chinese who infringe upon the legitimate rights and interests of foreigners. It handles civil and criminal cases in an appellate capacity when the people's procuratorate disputes the judgment or the defendant appeals against the verdict or ruling delivered by the people's court at the trial level.

There is no jury system in China. Instead, these judges are the theoretical decision makers. In serious cases (including most homicide cases) however, a judicial committee composed of the president, vice presidents, division chiefs and other leading officials of the court will decide the case. Thus, many lawyers lament that those who decide the case are neither familiar with the facts or the arguments, as they were not present at the trial. In some instances, the court itself is held accountable to the local communist party who will place pressure on the court to come to a particular decision in a case, therein demonstrating the glaring fact that China is well away from establishing an independent judiciary. However, the majority of criminal cases do not involve strong interests or concerns, thus judges are more free to make independent decisions, and lawyers to have a great impact on the case.